BY PHESHEYA KUNENE – EDITOR

EZULWINI – What happens when a farmer saves seed, a researcher isolates a gene, or a company develops a new product from a local plant, and who ultimately benefits?

That question sits subtly beneath the nation’s latest environmental reporting exercise, one that goes far beyond a single workshop and into the architecture of the country’s agricultural and scientific future.

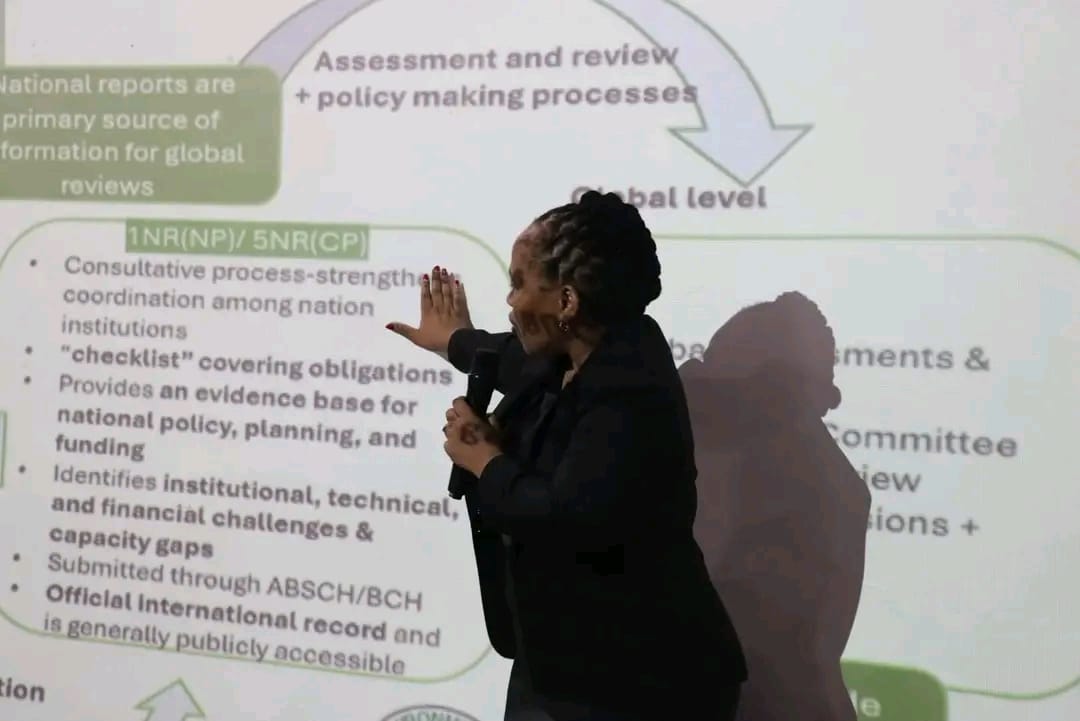

Eswatini has formally begun compiling its Fifth National Report to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety and its First National Report to the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing, a process that officials and experts alike describe as both a technical obligation and a strategic national reckoning.

The work was launched during an inception workshop held on 15 January 2025 at the SibaneSami Hotel in Ezulwini, convened by the Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Affairs through the Eswatini Environment Authority (EEA).

While the workshop marked the official starting point, the substance of the reports lies well beyond meeting rooms. At stake is how Eswatini governs living modified organisms, protects biodiversity, regulates biotechnology and ensures that genetic resources, many rooted in rural livelihoods and traditional knowledge, are not exploited without fair return.

The Fifth National Report addresses the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, the global framework that regulates the safe handling, transport and use of living modified organisms derived from modern biotechnology. The report builds on the Fourth National Report, which captured progress up to October 2019, and now documents national developments, enforcement capacity and emerging risks from October 2019 through to the submission deadline of February 28, 2026.

According to presentations made during the workshop, biosafety is no longer a niche environmental concern. It now intersects directly with food security, seed systems, trade access and farmer confidence. Countries without credible biosafety frameworks risk either uncontrolled exposure to biotechnology or exclusion from regional and international markets that demand regulatory assurance.

Running parallel to this is the country’s First National Report under the Nagoya Protocol, covering an eight-year period from November 2017. The Nagoya Protocol governs access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their use, particularly in research, breeding, pharmaceutical development and commercial agriculture.

For a country rich in indigenous plant species and traditional agricultural knowledge, the implications are significant. Without clear access-and-benefit-sharing rules, genetic resources can leave the country with little trace and even less return. The report seeks to document how Eswatini authorises access, protects community interests and ensures that benefits, whether financial, technological or developmental, flow back to rightful custodians.

Speaking on behalf of the Acting Principal Secretary, Wilfred Mbhekeni Nxumalo was reported as saying that the timing of the exercise was critical, as Eswatini is simultaneously preparing its Seventh National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. He indicated that aligning these reporting processes presents an opportunity to strengthen coherence across biodiversity-related instruments rather than treating them as isolated obligations.

Nxumalo further noted that the reporting exercise allows the country to assess how effectively its biosafety and access-and-benefit-sharing frameworks are functioning on the ground. He described the process as a strategic national stocktake, one that identifies gaps, institutional weaknesses and emerging community needs, while also strengthening coordination among stakeholders.

The EEA Executive Director, Isaac Dladla, was reported as having placed the discussion firmly in the lived reality of Eswatini’s people. He emphasised that nature remains central to livelihoods, from agriculture and medicine to cultural practices, and warned that undocumented or poorly regulated use of genetic resources exposes the country to silent loss.

Dladla stressed that proper documentation of national measures is essential to prevent unfair exploitation of biological resources, particularly where commercial or research interests are involved. He further indicated that strong access-and-benefit-sharing systems do not deter investment, but rather create certainty and trust for responsible actors.

Participants were repeatedly reminded that these reports are not the property of a single institution. Nhlangana Calisile was reported as having emphasised that national reporting is inherently multi-sectoral, requiring contributions from government departments, universities, private companies, research institutions and civil society organisations.

During technical sessions, stakeholders shared data sources, identified information gaps and clarified roles to ensure that the final reports reflect the full national picture.

For farmers and agricultural experts, the relevance of the process is immediate, even if often unseen. Biosafety frameworks influence which crop varieties are approved, how imported seed is assessed and how risks to local ecosystems are managed.

Access-and-benefit-sharing rules shape research partnerships, seed innovation and the protection of farmer knowledge in an era of accelerating commercial interest in genetic material.

Beyond compliance, the reporting exercise signals a shift in how Eswatini positions itself in a global system where biology has become economic capital. Clear biosafety rules support innovation without compromising safety. Transparent genetic resource governance ensures that development does not come at the cost of sovereignty or equity.

As climate change, biotechnology and food-system pressures intensify, the countries that thrive will be those with strong, credible governance frameworks underpinning their agricultural sectors. Eswatini’s decision to approach this reporting process as more than a procedural task suggests an understanding that biodiversity governance is now central to economic resilience.

In closing the workshop, government officials reaffirmed full support for the process, stressing that the credibility of the reports depends on accurate, honest data shared by all partners. That credibility, once established, will shape how Eswatini engages investors, researchers and regional partners for years to come.

Long after the workshop banners are taken down, the real work will continue, in laboratories, farms, policy offices and communities. The reports being drafted today will quietly determine how Eswatini protects life, manages innovation and ensures that the benefits of its biological wealth are not lost, but shared.