BY PHESHEYA KUNENE | EDITOR

MBABANE - Foot-and-Mouth Disease is no longer just an animal-health emergency in Eswatini. It has become a test of state capacity, farmer discipline and scientific judgment.

At the heart of the country’s response now lies a crucial question, not how fast government can vaccinate, but whether it is vaccinating the right disease.

That question explains the return of the Botswana Vaccine Institute (BVI) to Eswatini. Represented by veterinary epidemiologist Dr Tshenolo Pebe, BVI is on a technical mission to identify the exact strains of Foot-and-Mouth Disease currently circulating in local herds. The findings will determine the vaccines used in the national rollout planned for February 2026.

Agriculture Minister Mandla Tshawuka confirmed this during a press briefing in Mbabane earlier today, describing strain identification as a “critical scientific step” in preventing misdirected vaccination and prolonged market disruption.

In disease control, precision matters. Foot-and-Mouth Disease exists in multiple strains, particularly SAT-type variants common in Southern Africa. Vaccinating without confirming the strain risks wasting millions and offering false security to farmers.

Dr Pebe is expected to collect samples from outbreak zones in the Shiselweni Region, including Zombodze Emuva and Makhondza, and visit affected communities as part of the assessment. Botswana’s experience gives her work regional weight. The country has long relied on targeted vaccination, strict zoning and surveillance to protect its export-driven beef industry.

For Eswatini, the stakes are just as high.

Once a country adopts mass vaccination, the pathway back to internationally recognised FMD-free status becomes longer, more complex and more expensive. This is why veterinary experts across the region often favour rapid containment and movement control before large-scale vaccination is triggered.

This concern is already being voiced by farmers themselves. Reacting to the ministry’s update, farmer Thabo Dube warned that vaccination, while protective, carries long-term trade consequences.

“Mass vaccination plays an important role, but once introduced, regaining FMD-free status becomes significantly longer and more demanding. Rapid containment and strict control are safer if the country wants to preserve its standing,” he said.

That argument reflects a deeper tension now facing government, balancing urgent disease control against future market access.

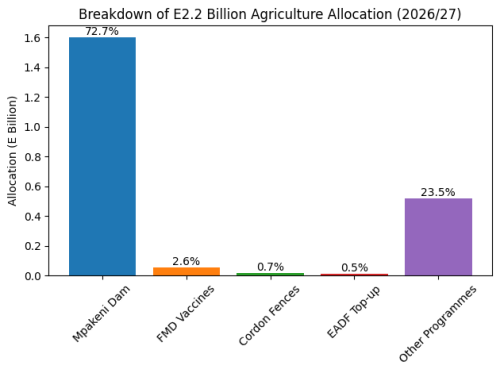

Despite these risks, Eswatini is moving ahead with mass vaccination. Government has allocated approximately E90 million to the programme, including E38 million already spent and an additional E57 million approved by Parliament. Tshawuka revealed that E5 million has already been paid for the first vaccine order, with delivery timelines expected to determine whether the rollout begins earlier than February.

The decision has been shaped by geography as much as policy.

Poor fencing along Eswatini’s borders with South Africa and Mozambique continues to undermine containment efforts. Uncontrolled livestock movement remains the single biggest driver of reinfection, a problem worsened by South Africa’s ongoing struggle with SAT 3 strains.

Tshawuka did not mince his words. He condemned illegal livestock movement, warning that it threatens to reintroduce the disease even after vaccination and renders scientific interventions meaningless.

“Compliance is not optional,” he said, urging communities, livestock traders and farmers to work with veterinary authorities rather than against them.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation is assisting government with fencing projects along key border areas, but officials admit infrastructure alone will not solve the problem. Behaviour, enforcement and community cooperation are just as critical.

Farmers across the country are watching closely. In Shiselweni and the Lowveld, movement restrictions have already disrupted sales and household income. In the Highveld, concerns centre on access to abattoirs and clarity around post-vaccination marketing.

The ministry has urged farmers to take vaccinated cattle to abattoirs for slaughter and inspection, arguing that this allows farmers to earn income while reducing infection pressure within communal herds. The longer-term aim is herd regeneration, replacing older stock with healthier animals and breaking the cycle of disease.

Tshawuka also confirmed that government is engaging South African authorities, including the Ministry of Home Affairs, to address cross-border livestock movement. Officials say the talks are progressing positively, though timelines remain uncertain.

What distinguishes this phase of the outbreak is the shift toward science-led control. Dr Pebe’s work will guide vaccine selection, surveillance strategy and containment priorities. In regional animal health, that level of technical accuracy often determines whether outbreaks are ended or endlessly managed.

Foot-and-Mouth Disease thrives on gaps, weak borders, illegal movement and delayed decisions. Eswatini’s challenge is to close those gaps faster than the virus can exploit them.

The outcome will shape more than animal health. It will define farmer livelihoods, export credibility and the future resilience of the country’s beef industry.

For now, the message is clear. Vaccines matter. But science, discipline and cooperation matter more.