Photo: Henning Naudé, Farmers Weekly

SIBUSISO MNGADI | CHIEF EDITOR

MBABANE – As South Africa rolls out a stringent 10-year strategy to contain Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD), the implications for Eswatini’s livestock sector are becoming impossible to ignore.

Across the border, South African Agriculture Minister John Steenhuisen has made it clear: FMD control will hinge on strict livestock movement controls, phased mass vaccination, and uncompromising biosecurity enforcement. For Eswatini, where vaccination is now imminent, the South African position sharpens an already delicate balancing act between urgent disease control and long-term market access.

Science Takes Centre Stage in Eswatini’s Response

This regional shift comes as Eswatini intensifies its own response. Earlier this week, Agriculture Minister Mandla Tshawuka confirmed that the Botswana Vaccine Institute (BVI) has deployed veterinary epidemiologist Dr Tshenolo Pebe to Eswatini to identify the specific FMD strains currently circulating in local herds.

The findings will determine the exact vaccines used in Eswatini’s national vaccination rollout planned for February 2026, a step Tshawuka described as “critical to avoiding misdirected vaccination and prolonged market disruption.”

Foot-and-Mouth Disease is not a single virus. In Southern Africa, SAT-type strains dominate, and vaccinating against the wrong strain risks wasting millions while giving farmers a false sense of security.

Dr Pebe is expected to collect samples from outbreak zones in the Shiselweni Region, including Zombodze Emuva and Makhondza, and engage affected farming communities as part of the technical assessment.

Lessons From South Africa’s Hard Line

At a media briefing in Cape Town this week, Steenhuisen outlined South Africa’s aggressive four-phase, decade-long FMD control plan aimed at restoring the country’s FMD-free status, lost in 2019.

Central to that plan are:

- Strict livestock movement controls

- Repeated vaccination in high-risk zones

- Digital traceability and electronic animal identification

- Possible enforcement support from police, military and traffic authorities

“FMD is not magically spread. It is spread through the movement of infected animals,” Steenhuisen warned.

KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng and parts of North West Province—regions bordering or economically linked to Eswatini—have been identified as priority vaccination zones, heightening the risk of spillover if cross-border movement is not controlled.

The High Cost of Vaccination Decisions

For Eswatini, the stakes are just as high. Once a country commits to mass vaccination, the pathway back to internationally recognised FMD-free status becomes longer, more complex and more expensive.

This reality is already troubling farmers.

Reacting to the ministry’s update, cattle farmer Thabo Dube cautioned that while vaccination is protective, it carries long-term trade consequences.

“Mass vaccination plays an important role, but once introduced, regaining FMD-free status becomes significantly longer and more demanding. Rapid containment and strict control are safer if the country wants to preserve its standing,” he said.

That concern mirrors debates currently unfolding in South Africa, where producers worry that prolonged vaccination could delay access to premium export markets.

Government Commits E90 Million as Borders Remain Vulnerable

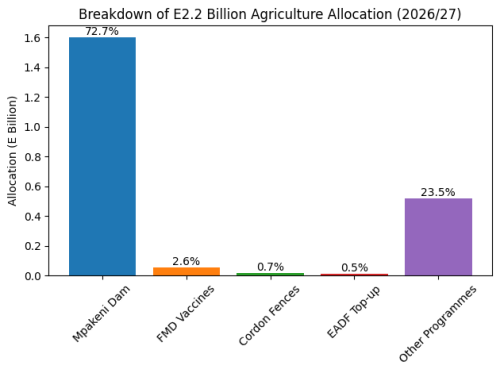

Despite these risks, Eswatini has committed firmly to vaccination. Government has allocated approximately E90 million to the FMD response, including E38 million already spent and E57 million approved by Parliament. Tshawuka confirmed that E5 million has already been paid toward the first vaccine order, with delivery timelines likely to determine whether vaccination begins earlier than February.

However, Tshawuka acknowledged that vaccines alone will not solve the problem.

Poor fencing along Eswatini’s borders with South Africa and Mozambique continues to undermine containment efforts. Illegal livestock movement remains the single biggest driver of reinfection, a challenge compounded by South Africa’s ongoing struggle with SAT-3 strains.

“Compliance is not optional,” Tshawuka said bluntly, warning that uncontrolled movement can reintroduce the disease even after vaccination, rendering scientific interventions meaningless.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation is supporting fencing projects along key border areas, but officials concede that infrastructure without enforcement and community cooperation will fall short.

Farmers Feel the Pressure on the Ground

Across Eswatini, farmers are already absorbing the impact. In Shiselweni and the Lowveld, movement restrictions have disrupted sales and household income. In the Highveld, uncertainty persists around access to abattoirs and post-vaccination market rules.

The ministry has urged farmers to channel vaccinated cattle through abattoirs for slaughter and inspection, allowing income generation while reducing infection pressure in communal herds. The longer-term strategy focuses on herd regeneration, replacing older stock with healthier animals and breaking repeated infection cycles.

Tshawuka also confirmed ongoing engagements with South African authorities, including the Ministry of Home Affairs, to address cross-border livestock movement. While discussions are described as constructive, timelines remain unclear.

A Regional Test of Discipline and Capacity

What distinguishes this phase of the outbreak is the deliberate shift toward science-led control. Dr Pebe’s strain identification work will guide vaccine selection, surveillance priorities and containment strategies. In regional animal health, such precision often determines whether outbreaks are eliminated—or endlessly managed.

Foot-and-mouth disease thrives on weak borders, illegal movement, delayed decisions and fragmented enforcement.

Eswatini’s challenge now is to close those gaps faster than the virus can exploit them.

The outcome will shape more than animal health. It will define farmer livelihoods, export credibility and the long-term resilience of the country’s beef industry.

For now, the message from both Mbabane and Pretoria is clear: vaccines matter—but science, discipline and cooperation matter more.