BY PHESHEYA KUNENE | EDITOR

EZULWINI - Scrapping agricultural and forestry certificates and diplomas is increasingly being blamed for paralysing skills development across the SADC region, with new research warning that the removal of these qualifications has weakened the practical training pipeline needed to support production. The findings suggest that reversing the scrapping of certificates and diplomas could be a key step in fixing the region’s growing farming and forestry skills crisis.

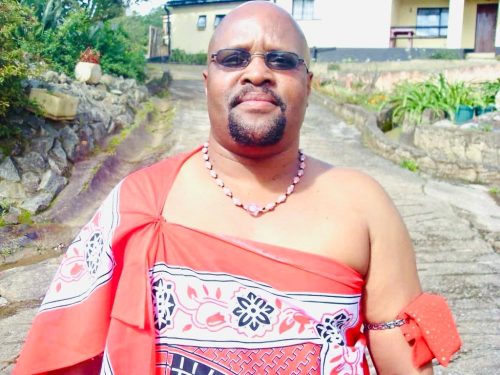

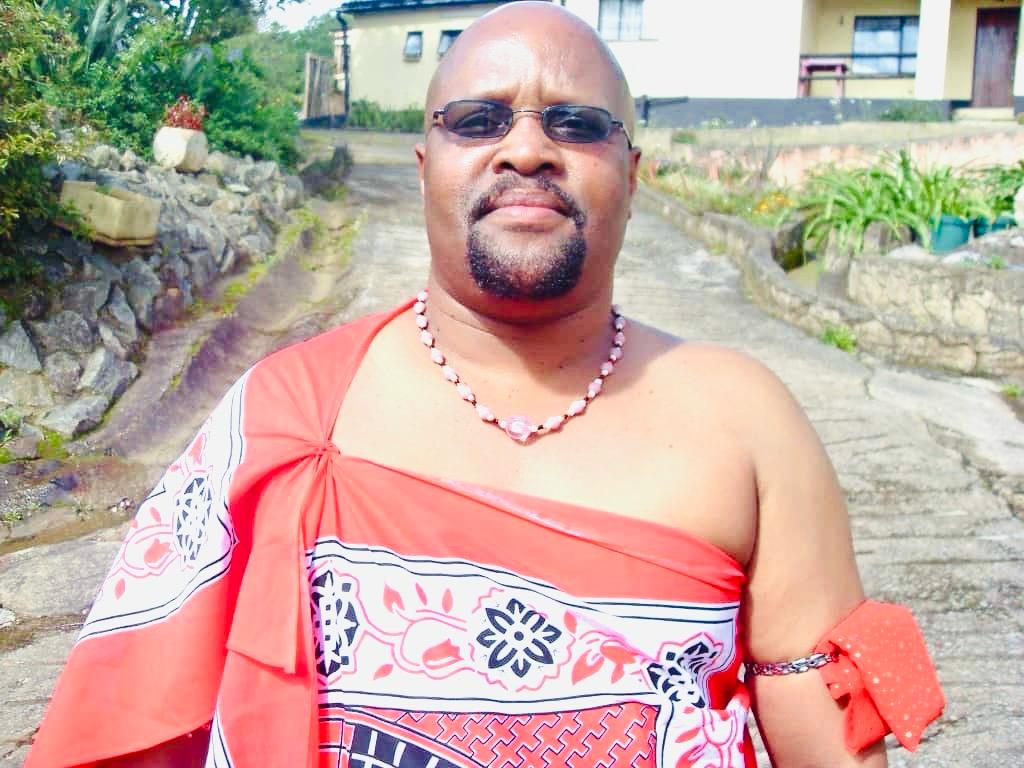

This emerges from a peer reviewed journal article published in Environmental Science Archives, authored by renowned agricultural scholars prof. Cliff Dlamini of Centre for Coordination of Agricultural Research and Development for Southern Africa (CCARDESA) and Stanley Dlamini, an agriculture and environmental consultant based in Eswatini.

The hard hitting study exposes what the authors call an inverted skills pyramid, a dangerous imbalance where universities produce large numbers of theory heavy graduates while farms cry out for irrigation technicians, mechanisation specialists, livestock supervisors and greenhouse managers.

CERTIFIED BUT NOT COMPETENT

Across the SADC region, agriculture employs more than 60 percent of the rural population and remains a backbone of GDP, exports and poverty reduction. Yet productivity continues to lag behind global averages, largely because the sector lacks field ready technical personnel.

In Eswatini, commercial producers say the gap is felt daily.

A Malkerns vegetable grower, Sipho Mkhonta, said farms were hiring graduates who could write business plans but struggled to calibrate irrigation systems.

“Give me a young person who can fix a drip line at midnight when the pump fails, not someone who only knows the theory of water management,” he said.

Livestock farmer Nomsa Dube from Siphofaneni echoed the frustration, saying many diploma level training programmes that once produced practical farm supervisors had disappeared.

“We are losing calves because there are few trained herd managers. A certificate does not vaccinate cattle, a skilled person does,” she said.

FARMS NEED HANDS, NOT FRAMES

The authors argue that the region has fallen into a qualification paradox, where framed certificates decorate office walls while fields remain short of skilled hands.

Employers report that many degree holders struggle with basic operational tasks, forcing farms to spend more on retraining or hiring foreign expertise, a cost that ultimately raises food prices.

Countries that retained strong vocational agricultural training such as Tanzania and Zimbabwe show better workforce balance and stronger technology uptake, proving that mid level technical education remains the missing link between research and production.

INDUSTRY VOICE

Eswatini National Agricultural Union (ESNAU) Chief Executive Officer Tammy Dlamini said the findings confirmed what agribusiness employers had been warning for years.

“We receive applications from graduates with impressive transcripts, but when you place them in a packhouse, dairy unit or irrigation block, many require basic technical retraining. The sector needs artisans, technicians and production supervisors as much as it needs researchers,” he said.

Dlamini added that the decline of structured vocational pathways was slowing the adoption of climate smart agriculture, particularly in protected cropping, precision fertiliser application and digital livestock monitoring.

YOUTH JOBLESS, FARMS SKILLS STARVED

The paper paints a troubling labour picture. Youth unemployment remains high across several SADC states while farms simultaneously report shortages of skilled workers, a mismatch driven by an education system that rewards theory over practice.

Diploma programmes once offered rural youth clear entry points into agriculture, but their decline has narrowed career pathways, fuelled urban migration and left an ageing experiential workforce struggling to adopt digital and precision farming technologies.

A CALL FOR TVET REVIVAL

The researchers propose a bold return to Technical and Vocational Education and Training as the backbone of agricultural transformation.

They recommend restoring autonomous technical colleges, introducing compulsory farm based apprenticeships, aligning curricula with industry needs and elevating vocational qualifications to the same status as university degrees.

Universities, they argue, should focus on research and high level innovation, while technical institutions produce the skilled workforce capable of operating irrigation systems, managing mechanised fleets and implementing climate resilient farming on the ground.

FOOD SECURITY AT STAKE

With climate change intensifying droughts, hailstorms and heatwaves across Southern Africa, the demand for precision irrigation, protected cropping and digital farm management is rising faster than institutions can supply skilled operators.

Without a decisive pivot toward skills based training, the region risks importing expertise while exporting unemployed graduates, a scenario that threatens productivity, youth livelihoods and long term food security.

For farmers like Mkhonta and Dube, the solution is simple and urgent, bring back practical training and put tools back into young hands.

As the journal concludes, agriculture’s future will not be written in lecture halls alone, it will be built by technically skilled hands in the soil.