BY PHESHEYA KUNENE - EDITOR

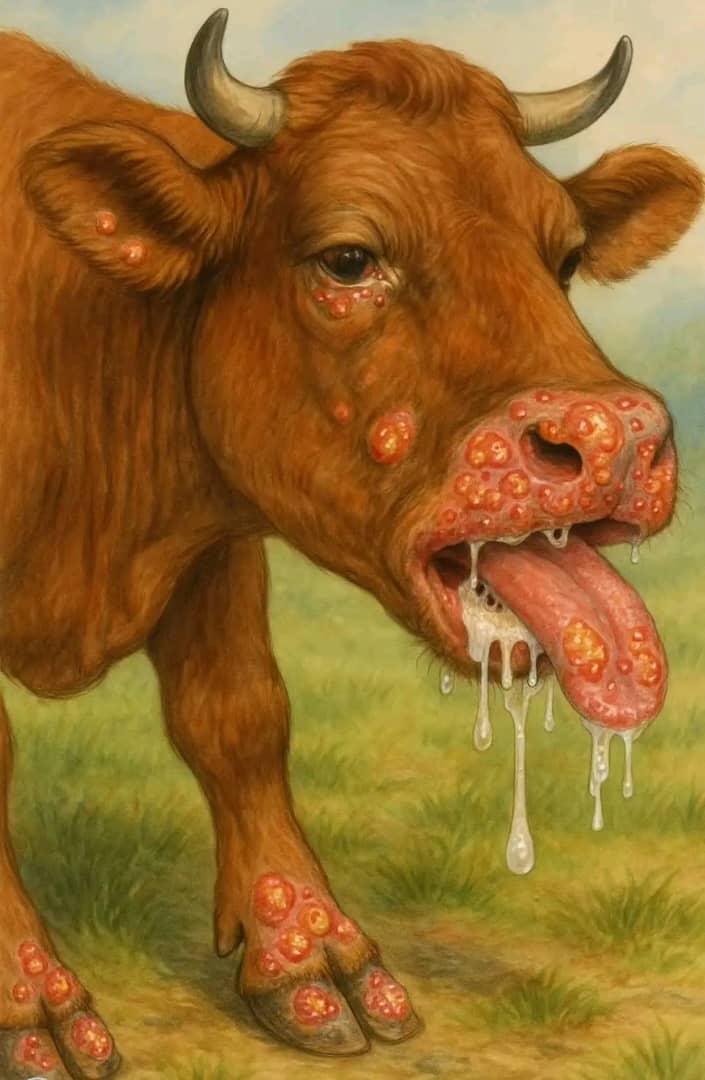

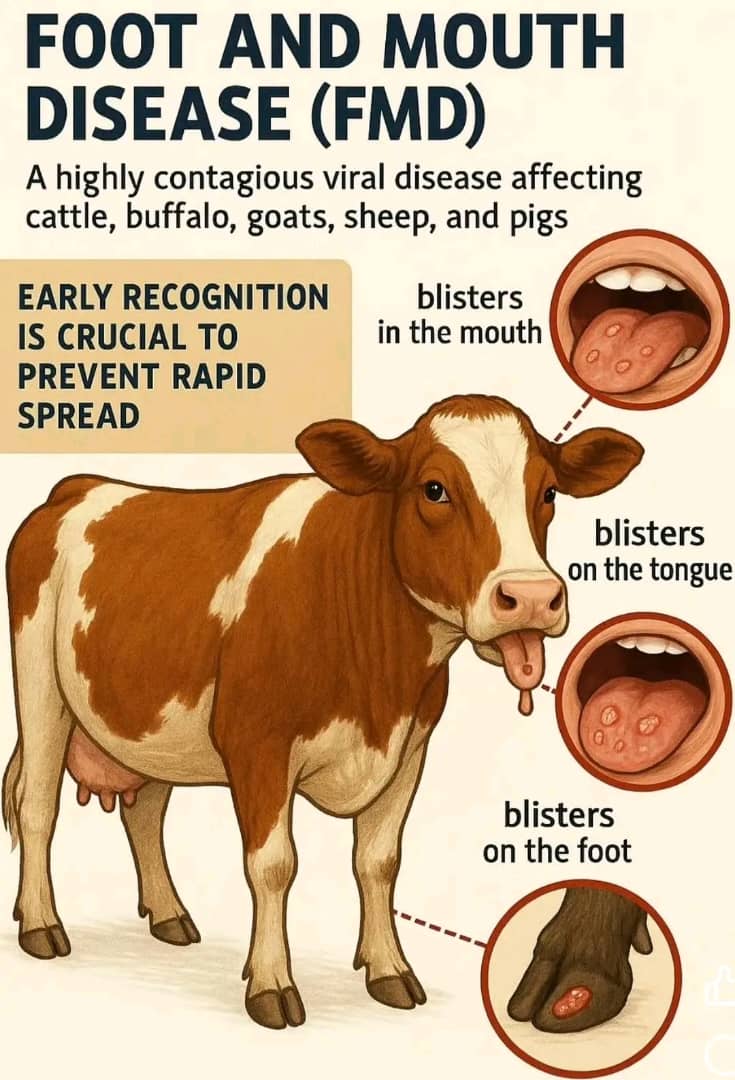

MANZINI – The confirmation that Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) has breached both communal and commercial herds has pushed Eswatini’s livestock sector into one of its most precarious moments in recent years. What began as a regional animal health incident has escalated into a national economic and food security challenge, exposing long-standing structural weaknesses in disease control, border management and farmer support systems.

With confirmed cases reported in Shiselweni, Lubombo and Manzini regions and the threat now looming over Hhohho, Eswatini’s suspension of its FMD-free status has triggered immediate export restrictions, strict livestock movement controls and heightened surveillance. For a country where cattle are not only an economic asset but also a cultural and social pillar, the implications run deep.

A SYSTEM UNDER PRESSURE

The Ministry of Agriculture has attributed the outbreak largely to uncontrolled animal movement, porous borders with South Africa and Mozambique, and deteriorating veterinary infrastructure, including non-functional dip tanks and damaged boundary fencing.

Emergency response measures have since been activated. These include targeted vaccination campaigns in high-risk zones, livestock movement bans, temporary closure of livestock markets and intensified disease surveillance. However, officials acknowledge that implementation has been uneven, constrained by limited resources and overstretched veterinary personnel.

In several regions, small veterinary teams are responsible for vast geographic areas, complicating vaccination schedules and enforcement. Farmers have reported delays, fragmented communication and uncertainty about the duration of restrictions, further heightening anxiety across the sector.

MINISTER EASES SLAUGHTER SALES RESTRICTIONS

In a significant policy intervention aimed at easing pressure on farmers, Minister of Agriculture Mandla Tshawuka has announced that livestock sales for slaughter are now permitted nationwide, including cattle from FMD-affected areas, under strict regulatory conditions.

The Minister clarified that the measure is designed to balance disease containment with economic survival for farmers. “Farmers are permitted to sell livestock strictly for slaughter and not for breeding or farming purposes,” Tshawuka said. “All animals must be slaughtered at authorised abattoirs, and movement of livestock and meat must be accompanied by valid permits issued by the relevant authorities.”

He stressed that transporting meat without an official abattoir permit is prohibited, and that sales remain restricted within designated red zones to prevent further spread of the disease. Farmers have also been urged to work closely with local agricultural offices to ensure full compliance with the regulations.

The decision offers partial relief to farmers sitting on unsellable livestock, while maintaining biosecurity controls critical to regaining disease-free status.

FARMERS COUNT LOSSES

On the ground, the crisis has already translated into mounting financial strain. “We are sitting on cattle we cannot sell, yet we still have to feed them,” said a small-scale farmer from Lavumisa. “Some of us borrowed money expecting to sell cattle before Christmas. Now there is no income, but the costs continue.”

Commercial farmers warn that prolonged restrictions threaten to collapse interconnected value chains, affecting feed suppliers, transporters, abattoirs and informal traders.

The Swaziland National Agricultural Union (SNAU) has repeatedly called for clearer communication, faster vaccination rollouts and a transparent compensation framework for affected farmers.

“Without compensation, farmers lose trust in the system,” a union representative noted. “That is when illegal movement and smuggling begin, and that undermines disease control.”

MEAT PRICES AND FOOD SECURITY AT RISK

With slaughter capacity constrained, red meat prices have surged, squeezing urban consumers and dampening festive-season demand. Informal butchers and small traders have been particularly hard hit, with many forced to suspend operations.

Economists caution that prolonged disruption could permanently alter consumption patterns, pushing households toward poultry and imported meat, further weakening the domestic beef industry.

Beyond pricing, food security concerns are on unsellable livestock, while maintaining biosecurity controls critical to regaining disease-free status.

FARMERS COUNT LOSSES

On the ground, the crisis has already translated into mounting financial strain.

“We are sitting on cattle we cannot sell, yet we still have to feed them,” said a small-scale farmer from Lavumisa. “Some of us borrowed money expecting to sell cattle before Christmas. Now there is no income, but the costs continue.”

Commercial farmers warn that prolonged restrictions threaten to collapse interconnected value chains, affecting feed suppliers, transporters, abattoirs and informal traders.

The Swaziland National Agricultural Union (SNAU) has repeatedly called for clearer communication, faster vaccination rollouts and a transparent compensation framework for affected farmers.

“Without compensation, farmers lose trust in the system,” a union representative noted. “That is when illegal movement and smuggling begin, and that undermines disease control.”

MEAT PRICES AND FOOD SECURITY AT RISK

With slaughter capacity constrained, red meat prices have surged, squeezing urban consumers and dampening festive-season demand. Informal butchers and small traders have been particularly hard hit, with many forced to suspend operations. Economists caution that prolonged disruption could permanently alter consumption patterns, pushing households toward poultry and imported meat, further weakening the domestic beef industry.

Beyond pricing, food security concerns are longer just a veterinary issue. It is an economic, social and national concern demanding urgency, unity and resolve.

(COURTESY PICS)